These modified records stand as a response to the embedded ideologies present in ‘Black and White Minstrels’ records. As a long-time record collector who has spent his adult life

shuffling around in the musty carboard boxes of charity shops searching for lost gems and cheap drum breaks, I constantly came across ‘Black and White Minstrels’ records. The overt

racism embodied by these records was always arresting when I flicked past them, but often this feeling was further exacerbated by seeing their longevity as popular entertainment.

There were over 50 years’ worth of these records to be found in pretty much every single charity shop in the Northwest of England, their popularity was immense. The history of

‘blackface’ performers dates to the end of the American Civil War but was popularised in the mid 19 Century, with performers such as Thomas Dartmouth Rice whose performances

caricatured, demeaned and dehumanized people of African origin. This long-standing, extremely problematic tradition was turned into prime-time entertainment by the BBC who

created the ‘Black and White Minstrels Show’ in 1958, and ran for two decades until 1978. Throughout the 60s the show was gaining up to 16 million viewers a week, hence the

propensity of records to be found in the quotidian cultural archives of our charity shops. Professor David Hendy writes that it is hard to fathom why the BBC, ‘took so little account of

the offence caused by white performers blacking-up their faces on a peak-time TV show.’ Especially during a period of heightened racial tension, the global civil rights movement and

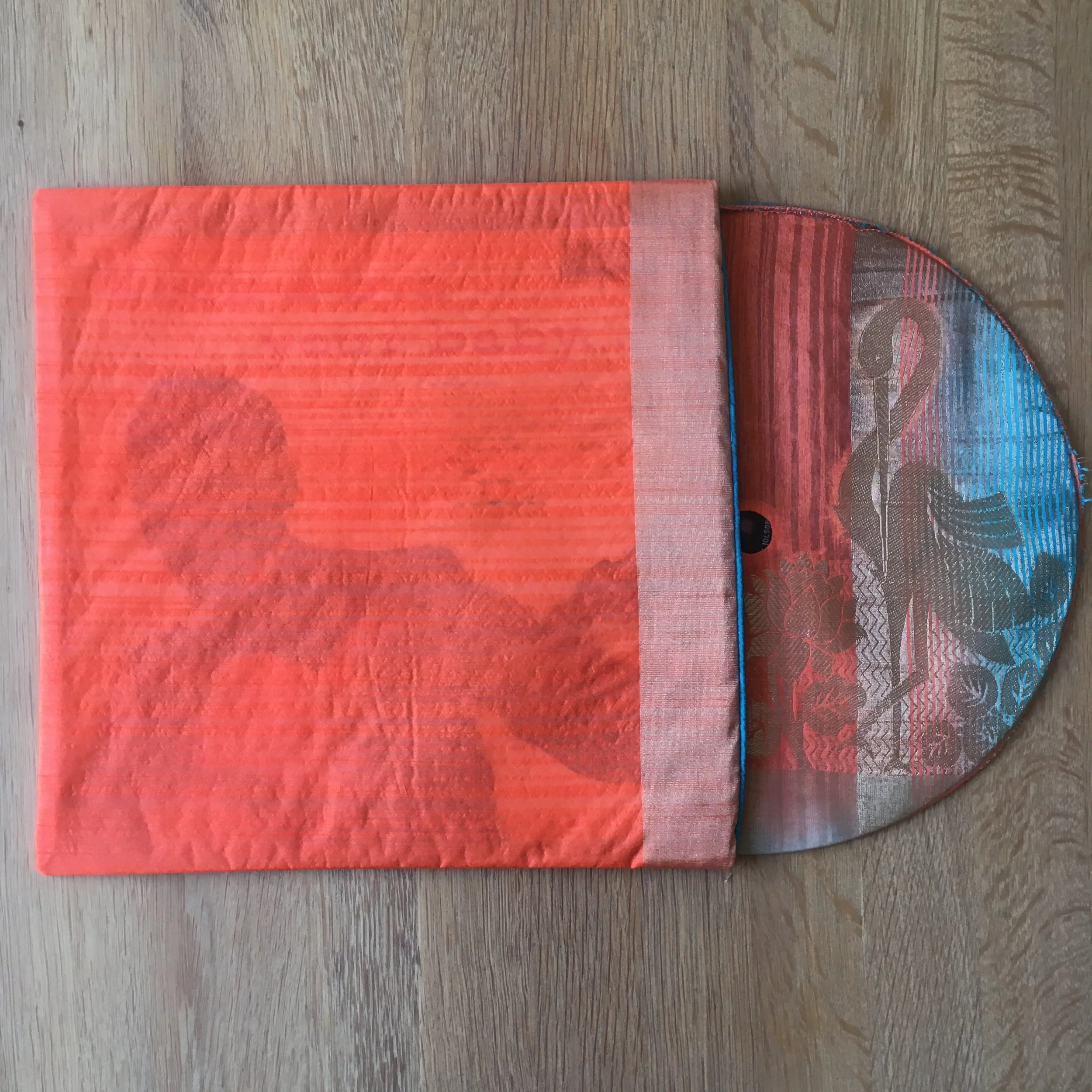

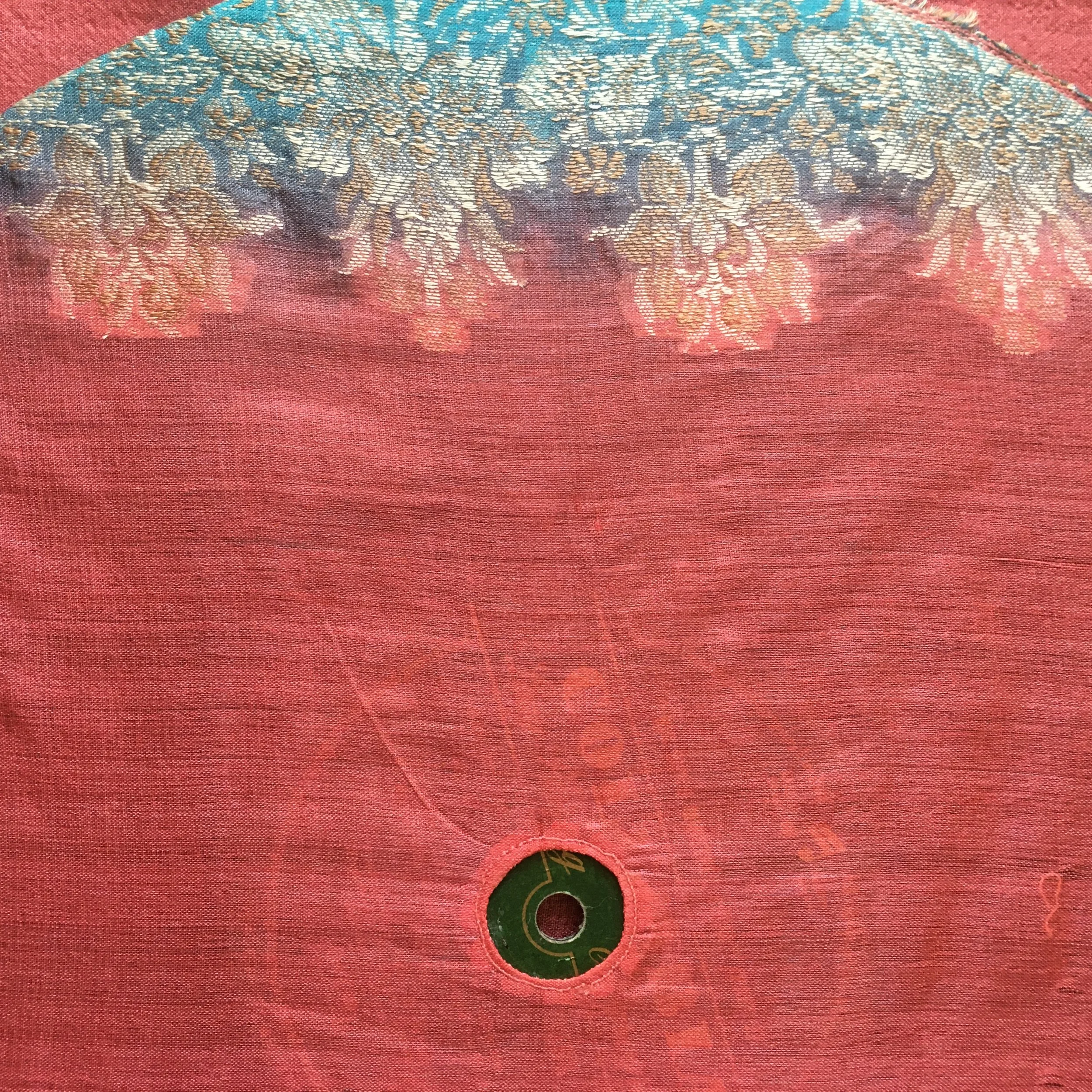

ever-changing demographics across our towns and cities. These two ‘Sari Records’ were created as elements of a collaborative sonic performance between Zimbabwean artist Masimba

Whati and myself for the closing of the British Textile Biennale. The work responds to some of ideas proposed by the artists in the Biennale around the politics of cloth, postcolonial identities,

and the irreversible entanglements inherent in our relationships with the migratory paths of human labour, industrialisation, technologies and culture, especially music. Our everyday lives

and relationships are enmeshed within the thousands of strands of our shared cultural heritages, which continuously intersect and overlap, creating ever increasingly complex

cultural spaces through which we navigate our identities, a process which is in constant flux. This brings me back to the records. Speaking of identity formation amongst the Windrush

generation, the first of whom started making their lives in the UK ten years prior to the first ‘Black and White Minstrels Show’ being aired, Prof Stuart Hall writes that migrants were

‘blocked out of any access to an English or British Identity, people had to try and discover who they were… In that very struggle is a change of consciousness, a change of self-

recognition, a new process of identification, the emergence into visibility of a new subject.’ (1991) These records speak to this idea of new and emerging post-colonial subjectivities laid

out against traditional ideologies. This coming together of newness through demographic change and the desire to maintain a status quo produces tensions but also great creative

productivities. New people inherently bring new materials which collide into what often seems like an inert cultural space. These bursts of cultural energy bring with them explosive

tensions but also the energy of change. These works have tried to capture some of these movements. Bringing together the idea of the ‘blackface’ as a manifestation of

institutionalised racist attitudes through disguise and humiliation with the power of autonomy exercised in dress. As clothes act as markers of cultural capital, identification, and

protection, but also play into ideas around disguise and visibility. So, by covering these records in sari fabric, given to me by my Mum and cousin, there is an attempt to reclaim

these problematic objects, to re-draw them. The symbolic act of erasing by covering rather than destroying, is to deliberately leave the palimpsestual residue of the original and

therefore to acknowledge the tensions inherent in the object, to bring into relief the struggle to give voice to the multivalent story of our shared histories.